Crashing Through the Median Barrier

If you want a measure of just how much Donald Trump has rolled a holy hand grenade into American politics (a lot of Americans don’t think that’s a bad thing) – and what that says about some of our deeper problems in American democracy (not everyone thinks American democracy is all that hot either) – look no further than this past week. It showed just how badly we need to erect more safeguards to keep our politics from spinning out of control.

To see why this week was such a canary in a coalmine, let’s first take a quick look at how American political campaigns decide on basic election strategy.

Campaigns track two factors among voters: how persuadable they are, and how likely they are to turn out to vote. These are important to understand because it’s a waste of both time and money to persuade people to be on your side who aren’t very likely to vote; and it’s actually counter-productive to get people to show up to vote who end up voting against you. Campaigns have limited resources: they need to make choices. How does a campaign decide how much time to spend on persuading people, and how much to simply get people who are already “persuaded” to actually vote? It’s not easy: there are different pathways to assembling the coalition of voters that put you over the “50% + 1” of the vote that you need for a majority.

And critically, the things you say and do to turn people out aren’t totally the same as the things you say and do to persuade. There can be tradeoffs: the kinds of messages that get people who are strongly on your side riled up and ready to head to the polls may turn off people in the middle. So you have to know the costs and benefits of focusing on persuasion versus turnout...and of focusing on the political middle versus your political base.

For a long time, there were enough “swing voters” – people who are enough in the center of the political spectrum that they could go either way – in many races that it was seen as a pretty good use of your resources to focus on trying to persuade them to be on your side. Nowadays, a lot of analysts think that there is a shrinking pool of truly persuadable voters so you should spend a bit more focus on energizing people to vote who are already probably with you. That’s been particularly true of midterm elections, like the one happening tomorrow (in presidential years, people are a lot more likely to show up to vote, whereas in smaller elections it tends to be the most motivated voters that turn out).

But, but, but…it’s almost never an all-or-nothing proposition. In every race there’s still some swing voters: people who will vote for one party in one election, and switch in the next; or who “split the ticket” and vote for people from both major parties in the same election. And the closer the race, or the closer the overall election across multiple races, the more that swing vote matters. As Vox points out, “there were 25 House Republicans who won reelection in 2016 despite Clinton carrying their district, plus 12 Democrats who won races in districts that voted for Trump.” That’s almost 10% of the U.S. House of Representatives who come from split ticket districts.

This is not a minor point. It’s a BFD. In close races, it’s the center that makes the difference. In close elections, it’s those close races that determine the balance of power. This is how in theory, in American Democracy, the center is supposed to exert control over the direction of our politics and the direction of our country, not the extremes.

Which brings us to last week.

Critics may deride President Trump for any number of reasons, but he has been awfully shrewd from the get-go about what works in politics these days. And he decided last week that going 100% after his base in the most incendiary way was the only strategy, even if it turned off swing voters and sent Republican House leaders into a panic. The caravan. Shooting people. The ad.

Yes, this was probably a calculated move to prioritize the Republican Senate majority over the House, but the simple fact remains that Donald Trump thought this was a viable political tactic in America today, the only viable tactic: forget the middle, aim as hard as possible for your base. He honestly thinks that this will preserve a Republican majority in the U.S. senate, and recent polls suggest that he’s right.

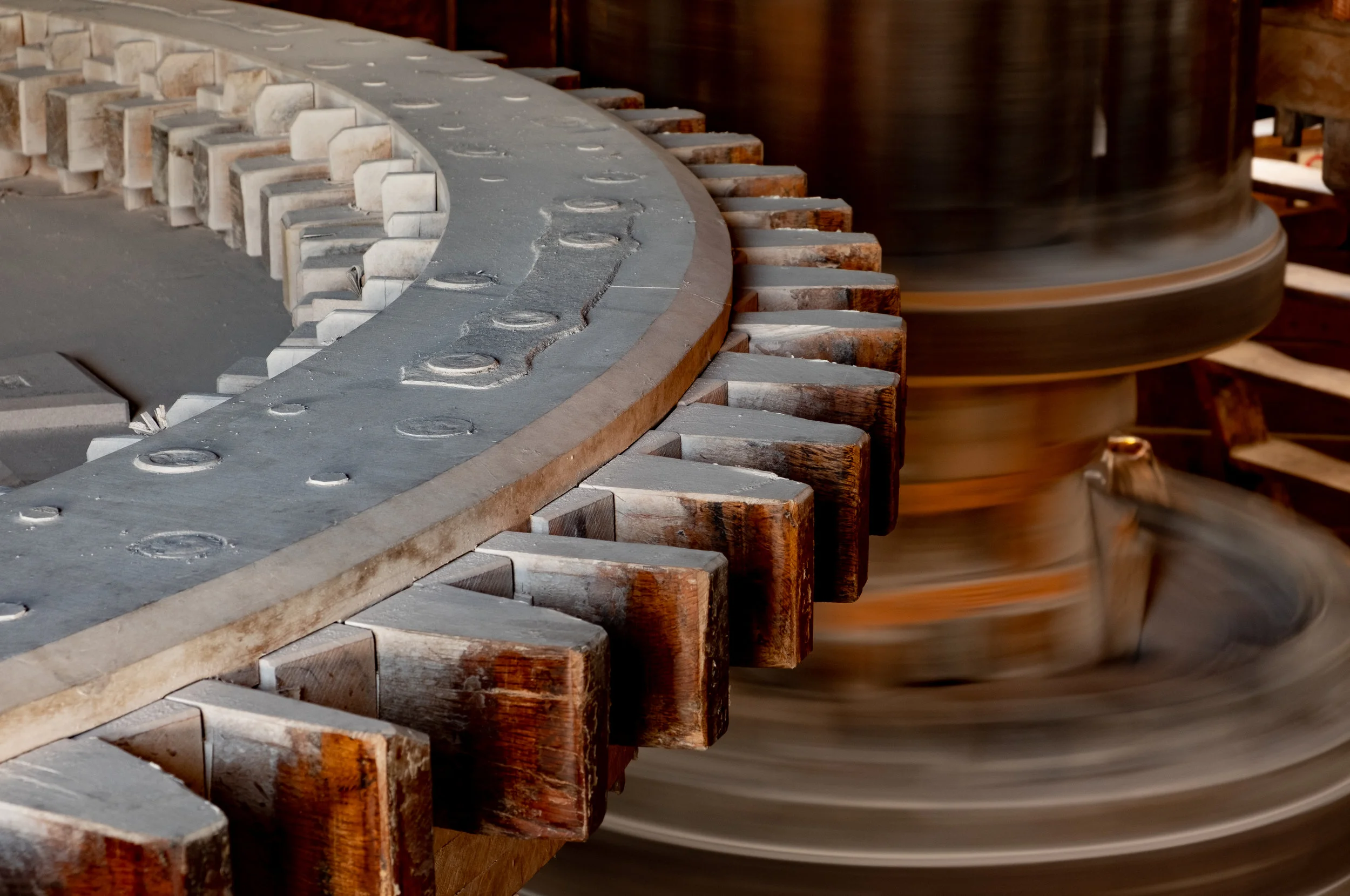

There’s a reason that we have median barriers to separate two sides of a road – specifically, to reduce the severity of crashes. The existence of significant numbers of swing voters, a true political center, used to be our median barrier in America politics…something that mitigated the inevitable collisions. Decisions to prioritize the base over the middle happened, but they were the exception rather than the rule, and there was usually at least some softening nod to the persuadable center. The fact that the President doesn’t think he needs to account for that is all the proof in the world that one of the key guardrails of our system is gone.

What should we do about it? We’ll return to that in the future. But if the natural protection of a true center that candidates need to cater to has faded, it means we need to find ways to erect new kinds of guardrails. If we don’t, all we’ll have left is the worst kinds of crashes.