The Rest is Commentary

The eyes of the political world are now turning to the upcoming Democratic presidential primary debates, the scythe in the Democrats’ Hunger Games. Debates in June and September will bookend a three month sprint of cattle calls and cable TV hits, and seem likely to result in a serious winnowing of the field by the Fall (dare we hope to the size of a starting baseball lineup?) as those failing to hit the party’s tougher new debate benchmarks lose hope of traction.

This is where the real primary campaign begins, and if you believe that Donald Trump represents a fundamental threat to the country, the stakes couldn’t be higher. Which puts a premium on the following question: how should Democrats – both candidates and voters – approach this process in a smart way, to achieve a good result?

By focusing on the one core issue that matters, and letting everything else go.

There is good provenance for this approach. The Talmud – the core text of Jewish law and theology – tells the story of Rabbi Hillel. When challenged by a potential convert to teach him the whole Torah (the Old Testament), he replied: “That which is hateful unto you do not do to your neighbor. This is the whole of the Torah, the rest is commentary.” Since the Talmud goes on to examine every aspect of life in exhaustive detail across 6,200 pages, this is a pretty telling comment about the value of getting to what is essential, and not being distracted by the rest, however compelling it may feel.

So first, what distracting “commentary” can Democrats dispense with in the coming months? Here are three big pieces of chaff:

Moaning about the Process: Many Democrats (especially those supporting candidates likely to be on the outside looking in) continue griping about the DNC’s rules for inclusion in the second round of debates or this year’s overall primary process. Some of this is a holdover from 2016 and the perception, perhaps misperception, that the party had a meaningful thumb on the scale for Hillary Clinton. Whatever flaws they see, they need to get over it. A consolidation needs to happen – a Democratic field of 24 “serious” candidates does the party no favors, as the Republicans painfully learned watching 15 candidates bicker while Donald Trump built unstoppable momentum. The psychologist Barry Schwartz has compellingly shown that anything over ten options or so only makes the burden of choice harder. And nothing is to be gained by prolonging this liminal period of water-treading before the top-tier can really work to break through with the voters they will need to motivate to win in 2020. Yes, there are flaws…it is certainly true that debates themselves are a poor way of choosing candidates, since the skill set involved in a TV debate has little overlap with the skill set required in governing. But the DNC’s approach at least requires the candidates to demonstrate skills that are correlated nowadays with winning – building a broad following in real life and on social media, presenting well on TV, and raising money. All things considered, it’s probably the least bad system they could have devised.

Twitter Noise: As a thought experiment, try this: give your best argument that more good than bad has come of Twitter. Is it even close? Personally I struggle to enunciate the “good” case, whereas here are just a few notables from the “bad” side. Twitter is of course Donald Trump’s preferred means of gaslighting America and trying to provoke Democrats’ outraged responses. He knows full well that Democrats could (and if they are undisciplined, will) spend the rest of the campaign responding to the President’s latest tweet insanity of the day, and nothing would make Trump happier, because then he would then be steering them to his most favorable strategic grounds (no collusion! I made a deal with Mexico! Millions of illegal immigrants voted!). Almost equally as bad is the grating sound to most Americans’ ears of the kinds of sentiments that dominate the Democratic Twitter echo-chamber. Democrats on Twitter are actually totally unrepresentative of most Democrats – they are disproportionately much more liberal, white, college-educated, and into identity politics – but they are the loudest. And that does the party a major disservice – and Republicans a giant favor – by creating a misperception that both Republicans and Democrats have equally gravitated to the political extremes (the movement has been much more pronounced among Republicans, and it’s not even close). And of course, both the Trump problem and the Democratic Twitter problem have been gleefully exploited by Russian trolls and bots, leading top experts to conclude that, yes, Russia did help steer the 2016 election to Trump and are likely to again. The best that Democratic primary voters and candidates can do for now is tie themselves to the mast and ignore whatever is on Twitter, either from within the party or without.

The Identity Politics Morass: At every opportunity, Donald Trump cagily turns the fight to issues that drag people back to their political tribes, shrinking and shaping the electorate to maximize his chances of winning. Nothing helps him in his goal so much as the perception that Democrats are obsessed with political correctness, identity politics, and cultural liberalism. It doesn’t matter if it’s untrue, unfair, or unevolved (or a line obsessively pushed by Fox News). Life’s not fair, and the political reality is that it works. A simple shorthand for Democrats is this: if you’re talking about how to help working Americans economically, you’re winning (see below), if you’re talking about something else, you’re probably not.

So what, then, is the one core issue for Democrats to focus on? It’s the obvious one, the only one: which candidate has the best chance of beating Donald Trump.

As I’ve shown before, Democrats overwhelmingly prioritize winning in 2020, it’s the theory of how to do it that they disagree about. Some argue that what is needed is an outspoken liberal with “bold, transformational ideas” to excite the base. Some say that a black, Latino, or female standard-bearer would most mobilize those critical voter demographics. Some argue that a more centrist type would win back the Rust Belt trifecta that Democrats need to re-take the Electoral College.

I have my own take on each of these theories, best discussed in more detail in a future column, but one thing I do disagree with is the argument that the entire enterprise of deciding based on electability is a mistake, and that since history shows that major comebacks happen in primaries (Obama, 2007) and previously “unelectable” candidates ultimately win (Reagan, Clinton, Trump), voters should just pick who they like. Predicting who is going to be most electable may not be entirely possible, but letting go the rope altogether isn’t the right idea either. Not with so much on the line. And there are big clues that Democrats can use to help decide which candidate(s) would be most effective in 2020.

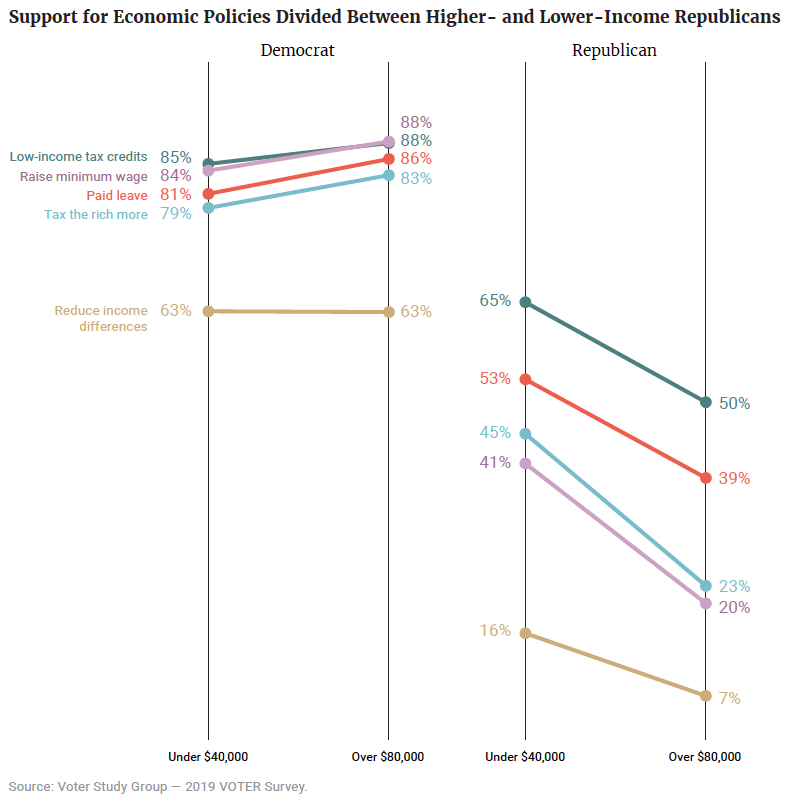

The best evidence is that the winning edge opportunity for Democrats lies in the economic case – and bear in mind that economic issues very much include affordability of health care, education, housing, and child care, in addition to (and perhaps more meaningful than) the more abstract numbers on unemployment, GDP, and overall prosperity. A recent Democracy Fund Voter Study Group’s 2019 VOTER Survey shows that “about one in five Republicans hold economic views more in line with the Democratic Party than their own party” while “Republicans with [those] more economically progressive views are less likely to say they will vote for President Trump in 2020 than Republicans in the economic mainstream of their party” and “Independents with economically progressive views voted for congressional Democrats by 16 percentage points more in the 2018 midterm elections than they supported Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election.” In other words – the exact voters Democrats need to get in order to win in 2020 (persuadable independents, turned-off Republicans) are reachable with economic arguments. And Democrats should know full well (see 2018 mid-terms) that their strongest ground is their economic pitch (part of why I argued in my last piece that they should not fear engaging despite relatively strong topline economic numbers – and that was before the even more recent dip).

So when you put it all together, what emerges is a reasonable guide for Democrats to use going into the next 90 days. Focus on how persuasively the candidates make an argument about how to extend economic prosperity to the middle class and those striving to enter the middle class. See how skillfully and quickly they can pivot away from the distraction issues – which is where the cable punditocracy and the Twittersphere will try to lead them – and onto core, winning issues. When you talk to other Democrats, focus on what matters about the candidates (is Joe Biden’s age really what you should be thinking about? Hint: if Fox News hosts are making it an issue, probably not – don’t give them rent-free space in your brain). If you see a cable show or a Twitter feed (or even a well-meaning friend) obsessing over the minutia of how progressive a candidate is (hint: they are all plenty progressive, and all would represent a massive improvement over Donald Trump for just about any Democrat), tune out.

Stick to the core. Let go of the commentary.